eBusiness Weekly

Borders define a nation. But who defined Zimbabwe’s 3000km-long boundaries?

What is a border?

A border is many things – a frontier, a margin, an edge. It defines belonging and at a national level, shapes identity and political consciousness.

As such the demarcation of such an important facet of human life occupied many states in the 19th Century during the heyday of colonisation with the attendant consolidation of control.

Borders define the limits of a state’s jurisdiction and political sovereignty and are hotly contested; wars have been fought for territorial claims and Zimbabwe, in this respect is no different to the rest of the world.

When did the border making begin?

The fascination with marking out territory and proclaiming it “mine!” seems to be a Western European preoccupation. Before the advent of colonisation, African states and empires had loosely defined boundaries, often favouring natural features or relying on the direct control of their armies over any surrogates.

Arguably, the land where people lived carried many intangible meanings and significances that were more important to the inhabitants than mere geography.

The boundaries of modern African states owe their origin almost without exception, to the influx of European empire-builders in the latter part of the 19th century, when after more than four centuries of contact, they laid claim to virtually all of Africa.

Parts of the continent had been “explored,” but now representatives of European governments and rulers arrived to create or expand African spheres of influence for their patrons. Competition was intense. Spheres of influence began to crowd each other. It was time for negotiation.

Where and when?

In late 1884, Otto von Bismarck, German Chancellor, called on representatives of Austria–Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, the UK, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden-Norway, the Ottoman Empire, and the US to take part in a Conference in Berlin to work out policy.

There is a common misconception that the main purpose of the conference was to allow the European powers to simply divide up Africa amongst each other. It is a common misconception that the Berlin Conference simply ‘divvied up’ the African continent between the European powers.

In fact, all the foreign ministers who assembled in Bismarck’s Berlin villa had agreed was in which regions of Africa each European power had the right to ‘pursue’ the legal ownership of land, free from interference by any other. The land itself – at least at the beginning – remained the legal property of Africans.

What did the Conference decide?

In some ways, Africa’s politico-geographical map is a permanent liability that resulted from the three months of ignorant, greedy acquisitiveness during a period when Europe’s search for minerals and markets had become insatiable.

Of relevance to this briefing, the General Act of the conference (easily downloadable online) fixed the following points:

An international prohibition of the slave trade was signed.

A Principle of Effectivity was introduced to stop powers setting up colonies in name only.

Any fresh act of taking possession of any portion of the African coast would have to be notified by the power taking possession, or assuming a protectorate, to the other signatory powers.

Which regions each European power had a exclusive right to ‘pursue’ the legal ownership of land (remember this would be “legal” in the eyes of the other European powers).

Explain the “Principle of Effectivity.”

This stated that powers could hold colonies only if they actually possessed them: In other words, if they had treaties with local leaders, if they flew their flag there, and if they established an administration in the territory to govern it with a police force or army to keep order.

The colonial power also had to make use of the colony economically. If the self-proclaimed colonial power did not fulfil these needs, another power could do so and take over the territory.

It therefore became important to get leaders to sign a protectorate treaty and to have a presence sufficient to police the area.

The clause resulted in the acceleration of the “Scramble for Africa” because there were numerous claims that had to be enforced on the ground. The result was a string of wars that went on for years.

Exploiting this clause would be an important part of Rhodes’ political manoeuvrings in 1890 against the Portuguese, the subject of part two of this briefing.

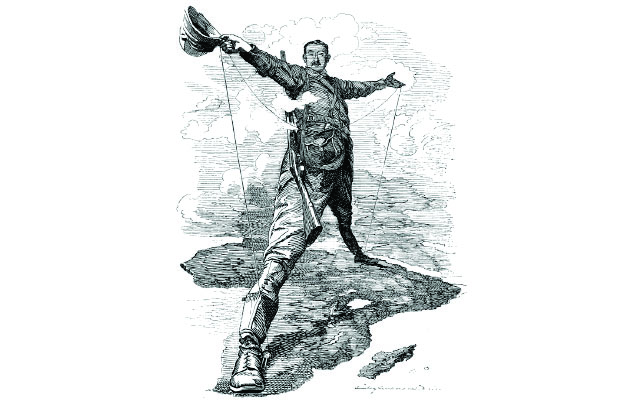

Enter Rhodes …

The story of Zimbabwe’s initial colonisation is well known so we don’t need too many details here. The story of the 1888 Rudd Concession and the Royal Charter granted as a result gave the concessionaires broad powers within “their” territory to act almost as they pleased.

In the second half of 1890 the occupation forces, under the command of the British South Africa Company (BSACo), marched into the area and took over – at least according to the maps they drew.

The occupation of Mashonaland brought the settlers into conflict with not only the Shona and Matabele but also with the Portuguese and potentially the Afrikaners.

How were the original borders defined?

The 1889 Royal Charter authorised the BSACo to operate in a vaguely defined area, extending into “the region of South Africa lying immediately to the north of British Bechuanaland, and to the north and west of the South African Republic, and to the west of the Portuguese Dominions.”

In 1891 further attempts were made to define the company’s territorial limits with some clarity in a proclamation that made reference to recognisable physical features.

The area was described in an Order-in-Council of May 1891 as “the parts of South Africa bounded by British Bechuanaland, the German Protectorate, the Rivers Chobe and Zambezi, the Portuguese Possessions, and the South African Republic”.

Did the conquest of Matabeleland change anything?

Following the defeat of the Ndebele kingdom by the BSACo troops in 1893, an Order-In-Council of July 1894 delimited the territory under the company’s jurisdiction as “the parts of South Africa bounded by the Portuguese Possessions, the South African Republic to a point opposite the mouth of the River Shashi, by the River Shashi and the Territories of the Chief Khama of the Bamangwato to the River Zambezi, and by that River to the Portuguese boundary, including an area of ten miles (16km) radius round Fort Tuli, and excluding the area of the district known as the Tati District”.

When were the territories amalgamated?

The Southern Rhodesia Order In Council, 20 October 1898 In October 1898 amalgamated the two provinces of Mashonaland and Matabeleland into the company-ruled territory of Southern Rhodesia.

The territorial extent of the new colony were defined as: “The parts of South Africa bounded by the Portuguese Possessions, by the South African Republic to a point opposite the mouth of the River Shashi, by the River Shashi to its junction with the Tati and Ramaquaban Rivers, thence by the Ramaquaban River to its source, thence by the watershed of the Rivers Shashi and Ramaquaban until such watershed strikes the Hunter’s Road (called the Pandamatenka Road) thence by that road to the River Zambezi, and by that river to the Portuguese boundary.

“The said limits include an area of ten miles radius round Fort Tuli, but exclude the area of the district known as the Tati district as defined by the Charter. The Territory for the time being within the limits of this Order shall be known as Southern Rhodesia.”

What happened to the “Disputed Territory”?

Relations between the Ndebele and the Ngwato, the largest of the Tswana tribes, were never good, mainly due to the brutality of the Ndebele during their migration through Ngwato territory in the late 1830s.

From that time, Mzilikazi and then his heir, Lobengula, regarded the Tswana as no more than their vassals, and thus felt that Ngwato territory fell under direct Ndebele jurisdiction.

King Lobengula and Khama of the Ngwato had argued over two strips of land, located broadly between the Zambezi and Shashi Rivers for many years. Within this region the main areas of contention were a narrow piece between the Shashi and Motlouse Rivers and an area around the gold-rich Tati District.

In fact Khama claimed his land stretched as far as the Gwaai River. Rhodes and the BSA Co argued that the land as far as the Makadikgadi Pans was in Lobengula’s domain and therefore came under the Rudd Concession.

So how did Zimbabwe lose out?

In the aftermath of the disastrous Jameson Raid, the British government became extremely wary of Rhodes’ motivations and intentions. Their failure alone prevented the British Government transferring administrative control within the Protectorate to the Company.

Decisively in late 1895, a delegation of chiefs from the Bechuanaland Protectorate had gone to London to seek a guarantee from the British government that their land would remain a protectorate and not be brought under the BSA Co. Colonial Scretary Joseph Chamberlain restored the northern territories of the Bechuanaland chiefs to the protectorate.

The agreement defined the limits of the tribal areas in the Protectorate, including that of Chief Khama whose northern boundary was described as “the Shashi River from the Tuli-Shashi junction to the source of the Shashi; thence a line running as nearly north as possible, so as to include Khama’s present cattle stations, to where that line will strike the Maitengwe River; thence along the Maitengwe to its junction with the Nata River, along the Nata to its junction with the Shua River, along the Shua River to where it joins the Makarikari Salt Lake”.

What about the rest of western border?

This was finally and formally delimited in Article 4 of the Southern Rhodesia Order in Council of 20 October, 1898. The boundary sector along the Pandamatenga road was demarcated by official commissions, first in 1907 and then in 1959.

The second commission was a joint one, involving police and representatives from both countries, with the main aim to revise and realign the boundary as it had been defined in 1907.

New beacons were made inter-visible (at a distance of 0.5km apart) along the old Pandamatenga Road. Pioneering use was made of aerial photographs to assist with relocating old boundary features, along with taking advantage of “local knowledge” to find the beacons from 1907.

And the Tuli Circle?

Described as “a settlement without a society [offering] only heat, fever, snakes and whisky,” Fort Tuli was established as the gateway to the country in early July 1890.

A thriving settlement developed in the area around Fort Tuli, especially once the safety of potential settlers and visitors from Ndebele attacks was all but guaranteed.

The perfect half-circle around Tuli originated in 1891 from a concession of land granted by Chief Khama to the BSACo.

The company wanted to use the land as a cordon sanitaire against indigenous cattle that might be infected with disease; unsurprisingly, Khama was of the same mind but with a view to the animals belonging to the whites!

The biggest fear was of deadly lung disease. The concession consisted of a piece of land south of the Shashi river and within a 10-mile radius of the fort on the south bank of the river at Tuli.

According to legend the radius for this distance was agreed upon using the average distance of a day’s waggon trek in this rugged area.

Some say that the radius was decided as the range of a cannon fired from the fort’s battlements, unlikely because the guns available at the time had far too short a range. Later, the Tuli Circle was recognised as part of the BSACo territory in Article 4 of the Southern Rhodesia Order in Council of 20 October 1898, and therefore within the territory of Southern Rhodesia.

The siting and construction of boundary beacons was not done until 1954.

What about the north and south boundaries?

Agreements reached between the British and the Boer-led South African Republic between 1881 and 1890 confirmed the Limpopo as the boundary between the Transvaal and the territory of Lobengula to the north.

In June 1891, a final unofficial attempt by a group of about 100 Boers from the South African Republic to establish an independent republic in the area of Masvingo province was halted by the company even before the main party had crossed the Limpopo.

Thereafter the southern boundary was secure. In the north, the Zambezi, from its confluence with the Chobe downstream to its confluence with the Luangwa river, was established as the boundary of Southern Rhodesia by the order-in-council of 1898 following the British government’s decision to establish a separate jurisdiction for Northern Rhodesia.

Did the construction of Lake Kariba change anything?

The boundary line along the Zambezi river in the area of the new Lake, was imprecisely defined until the promulgation by Britain of the Order-In-Council of December 20, 1963, a few days before the break-up of the Federation.

This clarified that the boundary was along the river, but also established a new one in the Lake, which had drowned the river channel. Except in the section within the lake, the boundary was now definitively demarcated to run along the exact middle of the Zambezi from the Mozambique border in the east to Kazungula in the west.

Within the lake, the boundary was demarcated by means of points identified by their latitude and longitude and joined together by straight lines. Nevertheless, the boundary within the lake closely follows the submerged river channel.

Are there any unresolved border issues?

By the end of 1891, less than a year after the occupation of Mashonaland, the general outline of the new country had already been set.

At a time when little of the country was known by the new colonial regime, physical features provided easily recognisable points of reference for the allocation of territory and the initial definition of the boundary.

Thus rivers came to define the boundary to a much greater degree than seems to be common for the rest of tropical Africa. Today, there are two major unresolved issues:

1. Most maps of the area of the Zambezi-Chobe confluence show the four international boundaries of Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Zambia converging near Kazungula. Yet the alignment of the boundaries in the Zambezi river in this area has never been resolved. The Botswana-Zimbabwe boundary is demarcated only as far as the south bank of the Zambezi River. Any projection of the boundary into the river would require the agreement of all four countries concerned as to the alignment of their lines into the water. This matter was in the news recently, due to the decision by Botswana and Zambia to build a 923-metre road and rail bridge at Kazungula, curved in the middle to avoid islands and territory claimed by Zimbabwe and Namibia.

2. It is still not established whether the boundary with South Africa follows the median line or the thalweg (the middle of the chief navigable channel of a waterway) of the Limpopo River.

Final thoughts (Part 1)

A major problem with modern boundaries is that they “often threaten to superimpose an unhistorical identity on African history.”

The consequence is that relationships between peoples can often be overlooked or over-emphasised. From a Zimbabwean perspective, prime examples of this skewed focus are the exploration of Ndebele/northern Shona relations while, for example, almost ignoring the relationships between the Ndebele-Tswana and Ndebele-Kalanga conflicts or forgetting that the eastern Shona kingdoms once covered a much larger area than considered today.

One hopes research into the mid-21st century will begin to explore these and other issues that arise out of our skewed border.

Part two of the border briefing will cover the convoluted, fascinating story of the eastern border.